Lesson 1: Hello Bioinformatics¶

Welcome to the Crash Course!¶

This course is designed for individuals with zero to some programming experience and zero to some bioinformatics experience. It is ideally offered as a series of in-person workshops, specifically for students at UC San Diego to enable them to do research and projects like modeling Cancer type from gene expression levels, and get some exposure before taking upper-div classes.

Regardless, we hope that the material here is useful even if you are not able to complete all the exercises.

- Sabeel Mansuri and Mark Chernyshev, Founders of the Bioinformatics Crash Course

Classic Bioinformatics Problems¶

As you progress through this course (and bioinformatics in general), you might find yourself developing technical skills without knowing what problems they can be used to tackle. In fact, there are several common (and difficult) problems in bioinformatics worth being familiar with. Therefore, this lesson will introduce you to of some of the things we, as bioinformaticians, do.

Note: In this course, we try to avoid lecture-based or text-heavy material. However, in this first lesson, we want to set a foundation of major problems bioinformaticians work on. We’ll keep it short, and move on to the interactive part: working in a Linux environment!

I. The Alignment Problem (full lesson)¶

The first problem we’ll look at is alignment. Alignment is the process of arranging sequences in a way to identify regions of similarity that may be a consequence of functional, structural, or evolutionary relationships between the sequences. In order to understand why alignment is hard and practical problem, we will start by learning a bit about sequencing DNA.

Illumina Sequencing:

This is the most widely used “golden standard” method of sequencing DNA. The main idea is that DNA is fragmented into pieces, attached to a flow cell, copied many times over by PCR, and the complement strand is determined one nucleotide at a time. The modified nucleic acids Illumina uses during the generation of complementary strands emit light when they are bound. Illumina sequencing adds one base, measures the color output of the flow cell, adds a different base, measures the color output and repeats over and over. Here is a nice graphic depicting the process:

There is also a video explaining Illumina sequencing which you’ll watch in every single Bioinformatics class you take in the future, found here.

Want to learn more about different sequencing methods? We have a document describing non-Illumina methods in more detail over here

Comparing Sequencing Methods and Why they Matter

What do all sequencing method have in common (yes, even PacBio)? All produce ridiculous quantities of small DNA sequences. Illumina produces 300 million to 4 billion reads per run, with a selection of read lengths ranging from 50 base pairs to 300 base pairs. Meanwhile, Sanger produces 50000 sequences at lengths varying from 800 to 1000 base pairs. To give some perspective, the typical animal of interest is a human and those have 3.0×10^9 base pairs. Individual human genes range from 1148 to 37.7 kb (average length = 8446 bp,s.d. = 7124).

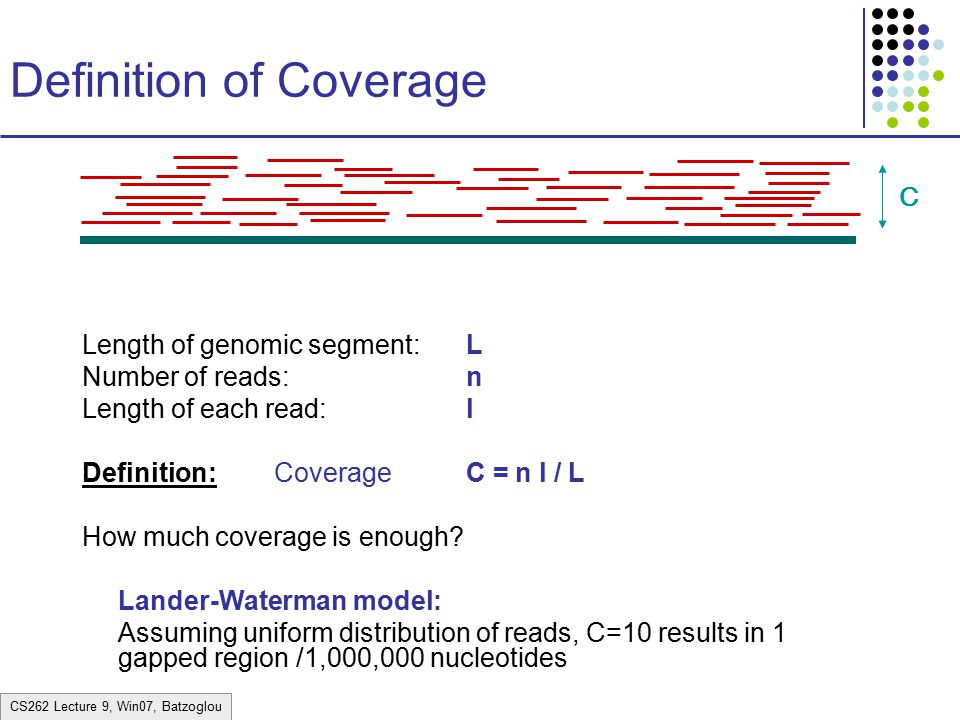

These tiny reads overlap all over the place. If you imagine the true sequence these reads came from and place the reads where they came from, you will get many reads piled up over every base pair in the true sequence. The more reads pile up, the more accurately you can predict the actual sequence. A common measure that rates the robustness of an alignment is coverage:

coverage

coverage

Besides helping us reconstruct the DNA put into a sequencer, alignment can also

- Determine which organism an unkown sequence comes from

- Pinpoint locations where mutations have occured relative to a reference sequence

- Help determine the evolutionary distance between sequences

TLDR: There are numerous complex applications of bioinformatics algorithms, from functional structure predictions to ancestral reconstructions. Alignment serves as the foundation for many of these algorithms, making basic sense of the incomprehensible mass of DNA that sequencing gives us.

II. The Clustering Problem (full lesson)¶

Clustering is the the process of assigning data points to groups in such a way that the elements in a group/cluster are more similar to each other than they are to those in other groups. The definition of what it means to be similar can vary and is determined by the function we use to measure distance between two points.

Some types of clustering:¶

- Hierarchical Clustering: Repeatedly combines the closest points into a cluster that is the hybrid location of both points. The reason this is interesting to us is that it forms a tree of clusters, which can represent a tree of related genes which can be used to infer homology.

hierarchical cluster

- K-means Clustering: Separates a dataset into k groups of points in such a way that the members of a cluster are as close as possible to the center of the cluster they belong to. This type of clustering can check that the datapoints we are observing cluster together by tissue type, experimental conditions, time points, etc.

- Fuzzy Clustering: Datapoints are not definitively assigned to a specific cluster, rather they are given a likelihood of belonging to a cluster. This can be used to ascertain levels of co expression between genes, revealing genes which may be under common regulatory control.

Aliview¶

Alright, enough of the conceptual stuff. Let’s get our hands dirty.

Note: The goal of this exercise is not really to master alignment. Instead, it’s more to get familiar with using bioinformatics tools and working with bioinformatics data.

Prerequisites¶

You will need Java to proceed. If you do not have it, go here and press the big red install button in the middle of the page.

Aliview is a sequence viewer with a bunch of built-in tools, including alignment tools. We will use Aliview to see what a typical dataset looks like coming out of the illumina sequencing machine and what it means, visually, to align the sequences. Click here and go to download the stable version for your OS.

Analysis¶

Next, download this neat dataset. Launch aliview, click file->open file->PC64_V48_small_reconstructed_seqs.fasta. Scroll to the right and notice the mess that begins to form as you scroll.

These sequences are sourced from the same gene and have gone through many cleaning steps, so the differences between them are quite likely to be real (rather than artifacts from sequencing). Click align in the upper left corner and click realign everything. Now scroll forward and observe the gaps that have been inserted by the aligner.

These sequences are actually from HIV-1 glycoprotein envelopes from a person with broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1(sequenced with PacBio). An effective HIV-1 vaccine should evoke the production of broadly neutralizing antibodies, so it is important to study the structure of the envelope that caused these antibodies to develop in individuals. The steps leading up to the data you downloaded allowed us to reveal a few specific strains. Now that we have them aligned, we can start asking questions about the differences between them and their evolution(which is important to figuring out how to counteract them). If you want to go into the nitty-gritty biology behind these sequences, go here. I will make a reconstruction of the evolutionary relationship for you to look at.

The SNP differences are obvious, but you will notice that there are weirder differences - like the >100 bp gaps formed in the middle. The truth is that I do not know why those are there! Those can be

- Real differences in hypervariable loops

- non-functional virions

- RT/PCR artifacts

Here’s another cool tool: Blast will quickly look up a sequence in the NCBI database and spit out similar sequences it finds. Now, go to aliview and click edit->delete all gaps in all sequences. Copy the first sequence into the clipboard. Google NCBI Blast and open up the first result. Paste the sequence into the big box in the top of the page and click BLAST at the bottom. After a few seconds, Blast should link you to a whole lot of glycoprotein that are… from the article these were published in! This is one of the basic uses of Blast - to figure out where a sequence comes from.